Post by /\/\att on Jun 19, 2007 12:47:14 GMT -5

Batman: The Complete History

by Les Daniels

Part One:

SHADOWS

Batman made his debut in Detective Comics #27 (May 1939), in a six-page story called "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate," which Bill Finger admitted was inspired by a Shadow story. It was a typical pulp murder mystery, but with all the excess verbiage removed (pulp writers were paid by the word, and it usually showed). Bob Kane's art was crammed into as many as eleven panels per page, and his style was still somewhat hesitant. "Of course the first sketches were very crude, but my drawing developed. Within six issues I elongated [Batman's] jaw, and I made the ears longer," said Kane. "I really improved fast. About a year later he was almost the full figure, my mature Batman."

"He can't stop bullets, you know," Bill Finger said of Batman, and that particular difference between Batman and Superman was demonstrated during "The Batman Meets Doctor Death," in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939). "Your choice, gentlemen! Tell me! Or I'll kill you," Batman threatens a couple of thugs, and seconds later the Caped Crusader gets shot. This third Batman story also introduced the series' first recurring villain (apparently killed in a fire, Doctor Death returned horribly burned in the next issue), and the hero's famous utility belt full of crime-stopping gimmicks. The script for this story has been attributed to Finger, but authorship was claimed years later by Gardner Fox, who is always acknowledged to have written the fifth and sixth Batman tales.

Fox would later script such characters as the Flash, Hawkman, Sandman, Dr. Fate, and the Justice Society of America, and his undisputed contributions to Detective Comics #31 and #32 also included some significant events. Batman was provided with a fiancée, Julie Madison (although she was soon forgotten), and with two new weapons. One was a stylized helicopter, "my Batgyro," as Batman put it, and the other was "the flying Baterang, modeled after the Australian bushman's boomerang." So Fox seems to have started the concept of Batman's ever expanding arsenal, and he also set Batman against the supernatural in this two-issue story. The villain was the Monk, who turned out to be a vampire, so Batman shot the bloodsucker and his sultry concubine with silver bullets. The business with guns was troublesome, and after one more recurrence DC's editorial staff decided to disarm Batman as far as deadly weapons were concerned, lest youthful fans take arms against a sea of troubles. The use of supernatural events would also be discouraged in the future, perhaps on the grounds that nobody should be scarier than Batman. He was a grim figure in his first years, casually killing criminals, and Bob Kane liked this dark version best-but it was not to last.

Part Two:

WINGS

In the days before television, movie serials were the equivalent of a TV series, with weekly chapters of less than a half hour in length being shown at local cinemas. They were intended for children and were generally not well made, especially by Columbia, which somehow ended up with the rights to both Batman and Superman. Batman isn't very good, but it's interesting as a cultural artifact. The villain is a Japanese spy named Daka (played by Caucasian actor J. Carroll Naish), whose hobby is turning Americans into mind-controlled "zombies," while his actual job is stealing radium for a device he calls an atom disintegrator. Considering that the war ended when the U.S. dropped an atom bomb on Japan, it's perhaps lucky that Batman and Robin were around, but there's something unpleasant about the film's attitude toward Japanese-Americans, and the narrator's smug announcement that "a wise government rounded up the shifty-eyed Japs."

Well, there was a war on, but there's no excuse at all for Lewis Wilson's portrayal of Batman as an upper-class twit, nor for Douglas Croft's smug performance that turns Robin into a kid you have to hate. These two can hardly be bothered to fight crime, and respond to a plea from Bruce Wayne's girlfriend, Linda Page (Shirley Patterson), by saying they'll attempt a rescue the next morning, when they've had time to pack. After a leisurely drive to the scene of the crime in a convertible that also serves as the Batmobile, and which has a little trailer in tow, the pair take a long pause to discuss the advisability of suiting up and going into action. Most of the serial is maddening in this manner, but it did provide a name and new emphasis for the Batcave, which the comics would then expand into the greatest hideout a kid could imagine. Apparently the writers were cave-crazy, since they also came up with a Cave of Horrors for Dr. Daka and a third cave that served as a radium mine. The serial was directed by Lambert Hillyer, who did much better by bats with his 1936 feature Dracula's Daughter.

Columbia waited until 1949 to release a second serial, Batman and Robin, but it wasn't much of an improvement. Many people think it's worse, and it was almost certainly cheaper, but it had a sturdier Batman in actor Robert Lowery, and at least this time there was no propaganda about inferior races. Instead there was a hooded villain called the Wizard, a serial stereotype but nonetheless not too different from several scofflaws who had shown up in the comics. This time the leading lady was Batman's latest flame in the comics, Vicki Vale (Jane Adams). Her brother, a bad apple named Jimmy, fell to his death wearing Batman's costume, which didn't seem to upset her much and at least was a fairly ingenious way of explaining how the Caped Crusader eluded doom at the end of one chapter. Spencer Bennet was the director, and the producer, famous for cutting corners, was Sam Katzman. The serials may have been "knocked out in about ten days," as Bob Kane lamented, but they reached millions and almost certainly increased sales of the Batman comics.

Part Three:

MASKS

In September 1965, Bob Kane wrote a letter to Batmania, an early Batman fan magazine, to announce that "ABC Television and 20th Century-Fox Films are jointly in the process of making an extremely high-budget color pilot of an hour-a-week Batman series that may wind up as two half-hour-a-week shows." Although success in any medium is unpredictable, Kane was extremely optimistic: "This is going to be the 'in' show to watch," he wrote, adding that despite Batman's widespread previous recognition, "the TV series will be the topper to it all." As it turned out, the program surpassed everyone's expectations and became an authentic phenomenon. Making its debut in midseason when such starts were rare, the series also broke precedent by appearing in a pair of half-hour segments broadcast on two different nights each week, and it seemed destined for a long run when both episodes placed among the top ten programs in the ratings. A genuine fad, the show faded as fast as it had flared, cutting back to one appearance a week and ultimately lasting a mere twenty-six months before it was canceled. Never before had a television series had such a meteoric rise and fall.

When Batman first aired, on January 12, 1966, the episode's villain was the Riddler. This hitherto minor bad guy was promptly vaulted into the pantheon of Batman's most famous foes, and the role turned a comedian and impressionist named Frank Gorshin into a star. The script, by Lorenzo Semple Jr., was based on a story that had appeared in Batman #171 (May 1965). In fact, there's a legend that TV producer William Dozier came up with the idea for the series after reading this issue on a transcontinental flight. Dozier, however, remembered that he was reading the comics because ABC had already acquired the rights to the character, and Bob Kane said the network became interested after one of their executives attended a showing of the 1943 Batman movie serial at Hugh Hefner's Playboy mansion in Chicago. Kane also recalled talking to Dozier and saying, "Why don't you have a cliffhanger like the Batman serials?" That idea was used, along with a pompous narrator like the one who had opened the serial (Dozier supplied the voice for the show). Another motivation for broadcasting Batman may have been the burgeoning Pop Art movement; galleries and museums were featuring works by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein that employed imagery derived from comics, including DC's. Warhol was a guest at the New York "discothèque frug party," which the network threw to celebrate the show's debut; also present was a fan dressed as Batman, who was uninvited but evidently too entertaining to eject.

The idea that something could be amusing because it was corny or ridiculous was essential to Pop and its allied aesthetic, camp; this was also the approach employed in producing the program. Some fans of the comic books were annoyed, but they were a minority compared with millions of adults who enjoyed feeling sophisticated, and millions of kids who didn't know or care that they were watching a spoof. And there was plenty to entertain them: the show had expensive sets, brightly colored costumes, a rocking theme song (by Neal Hefti), and lots of gaudy gadgets. Of these, the most memorable was the Batmobile, created for the show by car customizer George Barris.

Still, it was the characters that made Batman a success, and actor Cesar Romero recalls being told by the producer that "the important characters were the villains." Romero was a hit as the Joker, even if his white clown makeup had to be slathered over the mustache he refused to shave. The bad guy who appeared most often during the show's 120 episodes was Burgess Meredith as the Penguin. "It was kind of a trendy thing to do at the time," he said, but in fact he and Romero were among the first to battle Batman, and the show became fashionable only after their trend-setting performances. "I love the original crew of villains," said Bob Kane, including among their number Julie Newmar, who as Catwoman invested her role with an inimitable ironic eroticism. She was persuaded to take the part by her younger brother, a student at Harvard, and she credits some of her success to a Lurex costume that "had a kind of elasticity to it, so it gave where it was supposed to."

Part Four:

CLOAKS

Dennis O'Neil, just beginning to hit his stride in comics, had worked with Giordano at a small publisher called Charlton and was part of a group Giordano had brought with him when he was hired by DC. Comics eventually turned out to be the mainstay of O'Neil's career, but that wasn't part of his plan. "It was one of a number of things that I did as a freelance writer," he said. He thought of himself primarily as a journalist, and one of his strengths as a writer was his ability to make his stories seem like significant events and not just entertainments. This talent was especially notable later in 1970, when O'Neil and Neal Adams embarked on a groundbreaking series of stories that forced flagging heroes Green Lantern and Green Arrow to confront topical issues of the day, including racism and drug use.

No attempt was made to send an editorial message when O'Neil started on Batman, however. "It was just pure storytelling," he said, "just melodrama, and it didn't have any pretensions to anything else." O'Neil was born in the same month and year when Batman made his debut, which, he admits, "spooks the hell out of me when I think about it," especially in light of the impact the character eventually had on his life. After taking the Batman assignment, he studied comics that had been published when he was still a baby, in search of clues for creating a modern Batman. "We talked a lot, and it just came out that we wanted to go back to the way it used to be," said Julius Schwartz.

"Denny's writing style and my art style seemed to mesh perfectly," recalled Neal Adams. "We agreed on almost every detail of Batman's character. It was in 'The Secret of the Waiting Graves' that we first experimented, set the tone, and pointed the way." This story, for Detective Comics #395 (January 1970), presented Batman as a fish out of water, caught up in a Mexican horror tale about a wealthy couple who seek eternal life but end up crumbling into dust. This was a long way from Batgirl and the Batmobile, but, O'Neil said, "I'm sure we didn't give that a second's thought. I just wanted to make it Gothic and spooky. I was being influenced by writers like Lovecraft and Poe, and I didn't think about Gotham City."

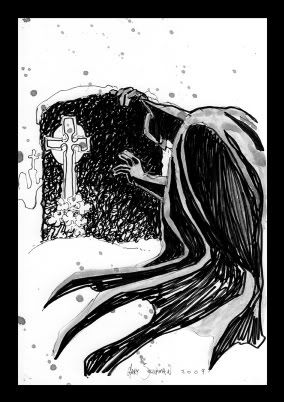

Several of the strongest stories created during this innovative period were set far afield from Batman's usual haunts. One of O'Neil's favorites, "The Vow from the Grave," in Detective Comics #410 (April 1971), was a carefully clued mystery in a rural environment, with a group of carnival misfits as murder suspects. Even more widely admired was "Night of the Reaper" in Batman #237 (December 1971). This tale of a killer dressed as the traditional robed figure of Death had a Halloween setting (recommended by artist Bernie Wrightson) and a background of Nazi atrocities (suggested by writer Harlan Ellison). The enthusiasm that such colleagues felt for this modern version of Batman was a tribute in itself, and Neal Adams responded with some of his most moody and evocative art. The most morbid of Batman's traditional foes, Two-Face, was revived after seventeen years of retirement in Batman #234 (August 1971), and the Joker reverted from clown to killer in Batman #251 (September 1973).

Almost inevitably, the innovators sought to introduce an original antagonist worthy to stand in the pantheon of his predecessors, and they came up with Ra's al Ghul, a mysterious figure whose passion was ecology and whose goal was world domination. He possessed the power to bring himself back from death, and he also had a lovely daughter, Talia, with whom Batman became romantically entwined. Batman's initial adventures with Ra's al Ghul constituted an epic that spanned the globe. "His face had to convey the feeling that he'd lived an extraordinary life long before his features were ever committed to paper," said Adams of this new character. "I created a face not tied to any race at all."

Another new bad guy, Man-Bat, had a simpler story and a more pronounceable name, which may account for his wider public recognition. Making his first appearance in Detective Comics #400 (June 1970), Man-Bat was Kirk Langstrom, a scientist and Batman fan who experimented with serums derived from bats and ended up taking on their characteristics. The result was a monstrous, pathetic creature who was nonetheless a genuine menace unless a cure could be found. In retrospect an obvious switch, Man-Bat hadn't occurred to anyone for three decades, but then the idea seemed to have many fathers. "There's a lot of talk about who created Man-Bat," said Julius Schwartz. "The Neal Adams version is not my version." Adams claims he came up with the character, but so does Schwartz. The late Frank Robbins, who wrote the origin story and also drew some later adventures in his angular style, might have had a third opinion.

Part Five:

SIGNALS

While the groundbreaking Knightfall saga was getting its start, Warner Bros. Animation was reinventing Batman in new cartoons created for television. Batman: The Animated Series had its premiere in September 1992 and immediately established higher standards for afternoon TV. An exceptionally stylish synthesis of the best elements from generations of comics and films, the show also benefited from striking character design, and came as close as any artistic statement has to defining the look of Batman for the 1990s.

When word first came down that Warner Bros. executive producer Jean MacCurdy had proposed an animated Batman series, artist Bruce Timm jumped at the chance. "I was like on fire and I ran back to my cubicle after the meeting and drew a page of Batman drawings in a theoretically animation style. I brought them to show Jean and she loved them," said Timm. "She put me and Eric Radomski in charge of doing a little two-minute pilot film, so we banged the thing together in a couple of weeks. It kind of impressed everybody, and on the basis of that she asked us to produce the show." Radomski had painted brooding views of Gotham City on black backgrounds, an unusual approach that proved especially effective. Against these film-noir settings, Bruce Timm placed characters seemingly inspired by comics creators like Kane, Robinson, and Sprang, with a more modern touch of Frank Miller thrown in. Timm, however, reduced these influences to their essence. "One of the things I learned over the years working in animation is that every time we were doing an adventure cartoon, there was always the drive to make the cartoons look more like comic books, and it really worked against what animation does best. The more lines you have on a character, the harder it is to draw over and over. I knew that simplicity would be better," Timm said, especially since the animation would be farmed out to different studios overseas where control would be difficult.

Shortly after the series went into production, Alan Burnett was brought in to serve as senior story editor and co-producer. His judgement about what would work for the show proved invaluable, and he also wrote superb scripts that included the television debut of Two-Face in (naturally) two parts, climaxing with Two-Face's breakdown when the coin he flips to determine his actions is lost in a hail of similar silver pieces. One of Burnett's best decisions was hiring Paul Dini, a writer and story editor who provided outstanding scripts like the Mr. Freeze episode "Hearts of Ice"; Dini eventually became so important to the show that he was promoted to co-producer. A unique contribution of the writing staff was to set the show in a mixture of different eras that mirrored the stylistic synthesis of Timm's character drawings. "If it had been up to me I would have set it literally in 1939," said Bruce Timm. "but writers find it really hard to write stories without falling back on computer screens and things like that." So in the series modern technology coexisted with 1940s roadsters and guys in trench coats. These unique choices by writers and artists gave the show a strong personality, and Timm adds that "a relatively high budget" made fuller animation feasible. Other assets included Shirley Walker's atmospheric music and an impressive cast of celebrity voices supervised by Andrea Romano. Batman: The Animated Series was so good that the Fox network also ran it for months in prime time to attract an adult audience, and the show went on to win multiple Emmy awards.

Batman: Mask of the Phantasm, a feature film based on the cartoon series, was shown in theaters in 1993, but didn't really find its audience until it was released on video as originally intended. Directed by Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm from a story by Alan Burnett, it seems to have been conceived as an animated answer to Citizen Kane, with specific shots inspired by the Orson Welles classic and a story about loss and the passage of time presented in a complex flashback structure. Yet it was perhaps the lighter moments that worked best, particularly a twist on the time-tested use of giant props that showed Batman battling the Joker throughout a miniature city designed as an old World's Fair exhibit.

The TV series evolved over the years, making more use of the Boy Wonder and eventually changing its name to The Adventures of Batman & Robin. The show went on hiatus after eighty-five episodes, while its creative team went to work on Superman cartoons, but Batman came back with a bang in 1997 when the WB network introduced The New Batman/Superman Adventures. The new hour-long show devoted half its time to each hero, except during "World's Finest," a ninety-minute tribute to the old comic book, which showed the Dark Knight and the Man of Steel working together. Modern tastes, however, dictated a certain amount of headbutting and one-upmanship before an uneasy alliance could be formed. The regular Batman episodes, with Superman nowhere in sight, nonetheless provided company for the Caped Crusader courtesy of a young new Robin, Tim Drake, and a revived Batgirl as well. For Bruce Timm, new episodes meant that "I could improve on the original style, because the more graphic and the more angular the designs are, the less they can screw around with them overseas. We've broken it down to even more of a mathematical formula." Timm admits that he "can't even watch" some of the widely admired early shows, but it's that perfectionist attitude that has made him a key figure in basic Batman.

book exerpts courtesy of dccomics.com